One of the distingushing features that has separated Web 1.0 from Web 2.0 has been the 'democratization' of information sharing. In the WWW's early years (the mid- through late 1990s), most content was in some way 'curated' by a webmaster or similar 'owner' who knew the password and the html coding necessary to 'put up' or 'post' information to 'their' website. There was, therefore, often a lag between the time that information was submitted and the moment when it actually appeared. There was also the possibility that information would be edited or even rejected if it did not conform to the website's policy. Gradually, however, many webmasters began incorporating emerging technologies into their sites that allowed visitors to upload information directly, without curation. Thus the age of user-generated content (UGC) began. With it, information curation became a reactive exercise. With it, anyone with an internet connection and the ability to upload or enter characters, became a content provider of sorts.

One of the distingushing features that has separated Web 1.0 from Web 2.0 has been the 'democratization' of information sharing. In the WWW's early years (the mid- through late 1990s), most content was in some way 'curated' by a webmaster or similar 'owner' who knew the password and the html coding necessary to 'put up' or 'post' information to 'their' website. There was, therefore, often a lag between the time that information was submitted and the moment when it actually appeared. There was also the possibility that information would be edited or even rejected if it did not conform to the website's policy. Gradually, however, many webmasters began incorporating emerging technologies into their sites that allowed visitors to upload information directly, without curation. Thus the age of user-generated content (UGC) began. With it, information curation became a reactive exercise. With it, anyone with an internet connection and the ability to upload or enter characters, became a content provider of sorts.

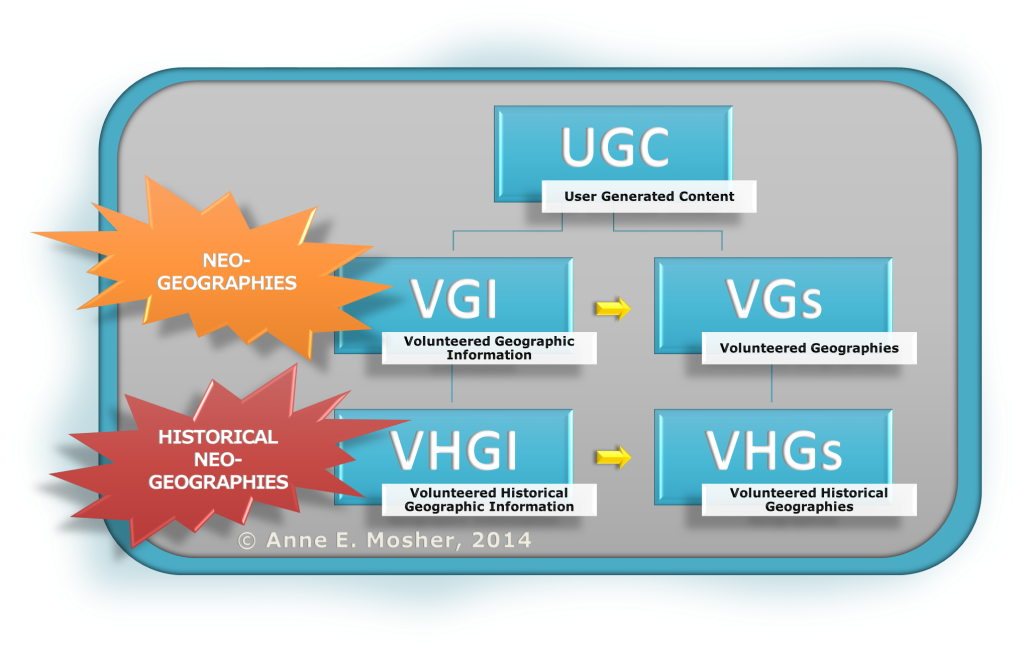

Over the past fifteen years or so, geographers have become increasingly interested in UGC, given that some of it is Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI). Typically, VGI is thought of as data that is generated by GPS-enabled smart handheld mobile devices. Device users create it when they “check in” or are tracked by apps and APIs (application programming interfaces) that monitor device movement. In turn, this information is sent to other platforms or technologies for storage, retrieval and analysis. Data analysts can then map VGI using the standardized spatial coordinate UTM grid system.

Desktop users can also generate VGI, too, as they did during the crowdsourcing imagery interpretation exercise hosted by DigitalGlobe to look for Malaysian Airlines Flight 370. When users clicked on a spot on the screen image, they activated the geocoded coordinates associated with that spot and the clicks were registered as “hits.” Proximate geographical coordinates that generated many user hits became, in turn, sites of interest.

Within this facet of my current research program, the VGI with which I am working is an example of the “desktop” variety (although with the development of mobile device apps for the platforms on which I work, that is changing). What makes this VGI special is that it is tightly coupled with “historio-temporal” information. The times and places when users log this information is definitely of interest, but the information that I am studying is embedded within the VGI content itself. This information refers to things that may have happened centuries ago. Some UGC is, therefore, Volunteered HISTORICAL Geographic Information (VHGI).

For example, when family historians compile, organize, and analyze birth and death dates and locations, marriage dates and locations, and residence dates and locations of individual kin, they are creating the basic data needed to construct a personal biographical profile for each person they study. In turn, many profiles can be linked to build a family tree. As family historians compile and organize such trees they are engaging in what might be viewed as a forensic reconstruction of kinship as well as a re-population of past places. When they do this using digital technologies and/or by working collaboratively online via Ancestry.com or FamilySearch.org, they are engaging in the practice of “historical neogeography.”

Ancestry.com members are doing historical neogeography in ways that go beyond mere data generation (collection, input) and curation (organization, editing, referencing), however. Some of them are using VHGI to produce triangulated written narratives that: first, track individuals through life, and, second, situate those individuals in relationship to specific geographical locations and historical events. Some members also track individual families over several generations and place them within the context of mass migrations.

These narratives (biographical and multi-generational) include quantifiable and objective elements that can be mapped.

Notably, the narratives are also sometimes very qualitative and subjective in what they include. They can describe what individuals and entire families thought about their lives-in-place. More often, the narratives convey what descendants believe to have been true about the times and spots where their ancestors lived. The narratives are expressions of a particular form of collective or social memory that Halbwachs referred to as “family memory.”[1]

Overall, many of these family memory narratives remind me of Michel de Certeau’s “spatial stories of the tour;” they follow a person or family along an itinerary—from stop to stop to stop.[2] At the same time, other family memory narratives describe synoptically the attributes of particular places in which relatives have lived (Certeau’s “spatial stories of the map”).

In some cases, family memory narratives break free from ‘mere’ description and venture into the realm of inductive and deductive logical reasoning. Ancestry.com members sometimes interpolate and extrapolate from the VHGI they have compiled to speculate on the reasons why deceased persons in their family migrated, stayed, and interacted with their surroundings as they did. Given that they are uploading these interpretive family memory narratives for other members to see, the narratives might be considered volunteered historical geographies (VHGs)

How do volunteered historical geographies compare to academic historical geographies? We (academic historical geographers and other geographers who trace change over space and time) tend to be driven by the desire to produce formal and reliable abstraction narratives. Such narratives are created in relation to various forms of theory and/or serve as a means to contribute to and resolve historiographic debates. Thus we erect our work, in part, on foundations of preexisting secondary literature with the expectation that the knowledge and abstraction narratives we produce will be added to that secondary literature. We are researchers standing on the shoulders of other researchers.

Ancestry.com members, however, seem to be driven by _____(?); a desire to know one’s “roots,” a desire to understand one’s place in the world, a need to belong to something geographically larger and historically longer than things perceived to be spatially smaller and temporally shorter. Although Ancestry.com members consult or quote (or plagiarize) secondary literature, there is no one set standard of practice or reason for doing this.

Furthermore, Ancestry.com members sometimes make their volunteered historical geographies incredibly personal and fill them with uncertain information, actions that—as authors—they will frequently acknowledge as part of the narrative. Granted, academic writing is personal and we can be candid, too, but the personal is something—even in this post-postmodern world—many of us try to downplay or neutralize through positivist objectivity, the third-person voice, or through discussions of positionality. Academic writing is also definitely filled with uncertain information and we frequently invoke conditionalities: “seems to be”, “the data suggests,” “sometimes, “often,” “it is plausible,” “could,” “might,” etc. In contrast, many VHG authors say, “This is probably wrong but,” “I am guessing that . . .” and “I don’t know why she did that but . . .” VHG authors will also use what they write as a way of asking for help with their work . . . similar to what I do when I blog.

Bottom line: there is a candor within VHGs that is simultaneous breathtaking and refreshing.

To study UGC, VHGI, and VHGs, my work explores a very specific class of Ancestry.com UGC: “public member stories.” Since 2007, Ancestry.com members have attached 12.2 million of these stories to some of the 5 billion “person profiles” that they have created. In turn, those person profiles have been incorporated into 55 million “family trees.” Anyone with an Ancestry.com subscription can read the stories, either as standalone texts or in the context of the biographical profiles and trees to which they belong. In this sense, the public member stories are an element in what I call a family history UGC information complex (Figure 1). All three major facets of this complex usually contain geographic information.

To study UGC, VHGI, and VHGs, my work explores a very specific class of Ancestry.com UGC: “public member stories.” Since 2007, Ancestry.com members have attached 12.2 million of these stories to some of the 5 billion “person profiles” that they have created. In turn, those person profiles have been incorporated into 55 million “family trees.” Anyone with an Ancestry.com subscription can read the stories, either as standalone texts or in the context of the biographical profiles and trees to which they belong. In this sense, the public member stories are an element in what I call a family history UGC information complex (Figure 1). All three major facets of this complex usually contain geographic information.

Public member stories offer exciting research possibilities for historians, historical and cultural geographers, textual studies scholars, anthropologists as well as social media researchers. The stories will be useful in addressing questions about:

- practices of collective/social/family memory

- kinship and relatedness;

- vernacular (in contrast to official) understandings of past places and events;

- travel writing in the digital age;

- the representational products of heritage and genealogical tourism;

- lay (in contrast to professional) representational expressions of history and geography awareness;

- the ‘digital immigrant’ generation’s engagements with Web 2.0 social media;

- digital historical geography, digital history and the digital humanities;

- academic and lay research in crowd-sourced, lay-curated archival environments; and,

- the ethics of human subjects research within the social sciences and humanities.

These are, at least, the major themes and issues that have emerged as I have systematically researched public member stories as a “Big Data” genre over the past two years.

@geodoctress Like your term historical neogeography, intrigued to learn it’s practiced via http://t.co/9FnPkdCFOs https://t.co/J8HNMoICWH